The Brumos Collection was never meant to feel like a conventional museum. From the moment you arrive, it’s clear this place was designed as a homage to a bygone era of American industry and motorsport. Housed inside a 35,000-square-foot red brick building inspired by the Ford Motor Company’s Model T and Model A manufacturing plant that operated in Jacksonville from 1924 to 1932, the facility immediately sets its tone. Large front windows and period-correct brickwork give the collection an atmosphere few automotive museums manage to achieve—equal parts factory floor, race shop, and time capsule.

Inside, the museum unfolds as one expansive space, thoughtfully divided by era rather than by brand or theme. Prewar machines occupy one side of the room, while the opposite end is dedicated to some of the most iconic Porsches ever built. Along the walls, life-size images of Ettore Bugatti and Harry Miller share space with Armand Peugeot and Fred Offenhauser, placing the cars within a broader narrative of innovation, competition, and engineering ambition that spans continents and generations.

The early automotive pioneers are well represented. Open-cockpit racers, historic engines, and period memorabilia fill the prewar section, surrounded by trophies and photographs from racing’s formative years. One of the standout exhibits chronicles the era of American board-track racing, preserving the legacy of the 24 wooden board tracks built across the United States in the early 1900s—a dangerous and spectacular chapter of motorsport history that has largely faded from public memory.

Greeting visitors near the entrance is a pristine 1925 Bugatti Type 35. In the 1920s, this model amassed more than 1,000 victories worldwide, becoming one of the most successful race cars of all time. The example displayed at Brumos is especially significant. Originally owned by Wallis Bird, heir to the Standard Oil fortune, the car spent more than a decade resting inside Bird’s Long Island estate garage. It was entered in just one race—the 1937 Automobile Racing Club of America Grand Prix—before changing hands twice and eventually finding its way into the Brumos Collection, where it later received a meticulous frame-off restoration.

The collection weaves personal history into its storytelling. The number 59 appears repeatedly throughout the space, a reference to Gregg’s service as a naval intelligence officer aboard the USS Forrestal, which carried the hull number 59. Subtle details like this quietly connect racing success to discipline, preparation, and service beyond the track.

The Porsche side of the collection opens with the Frontrunner display, positioned in front of “Buster,” the unmistakable Brumos team transporter. Built on a 1968 Mercedes-Benz bus chassis, Buster was far more than a transport vehicle. When it arrived at a circuit, it announced intent. Porsche had arrived to compete seriously. Within the museum, the transporter stands as a reminder that endurance racing is built on logistics, preparation, and presence just as much as outright performance.

From there, attention naturally shifts to the collection’s pair of Porsche 917s. One is a 917K dressed in unmistakable Gulf Racing livery, instantly recognizable to generations of enthusiasts. Although this chassis does not carry racing history of its own, it was used during the filming of Steve McQueen’s Le Mans, securing its place in motorsport culture. With approximately 630 horsepower and a weight near 1,800 pounds, the original 917 was ferociously fast but notoriously unstable at speed. After the 1969 season, John Wyer—now campaigning Porsche instead of the Ford GT40—pushed for aerodynamic solutions. The result was the upswept short-tail configuration, or Kurzheck, which delivered the high-speed stability the car desperately needed. The 917K was born and soon became dominant in the early 1970s.

Sitting alongside it is the 917/10, the K’s younger, turbocharged sibling. Built for the American Can-Am series, the 917/10 represented a turning point for Porsche. Competing in a championship with minimal restrictions and dominated by McLaren, Porsche took its Le Mans-winning 917 platform and fundamentally reengineered it. Turbocharging transformed the flat-twelve engine, adding immense power and complexity. The car reflected a broader shift within Porsche itself, as the company evolved from a small family operation into a larger, more structured engineering force.

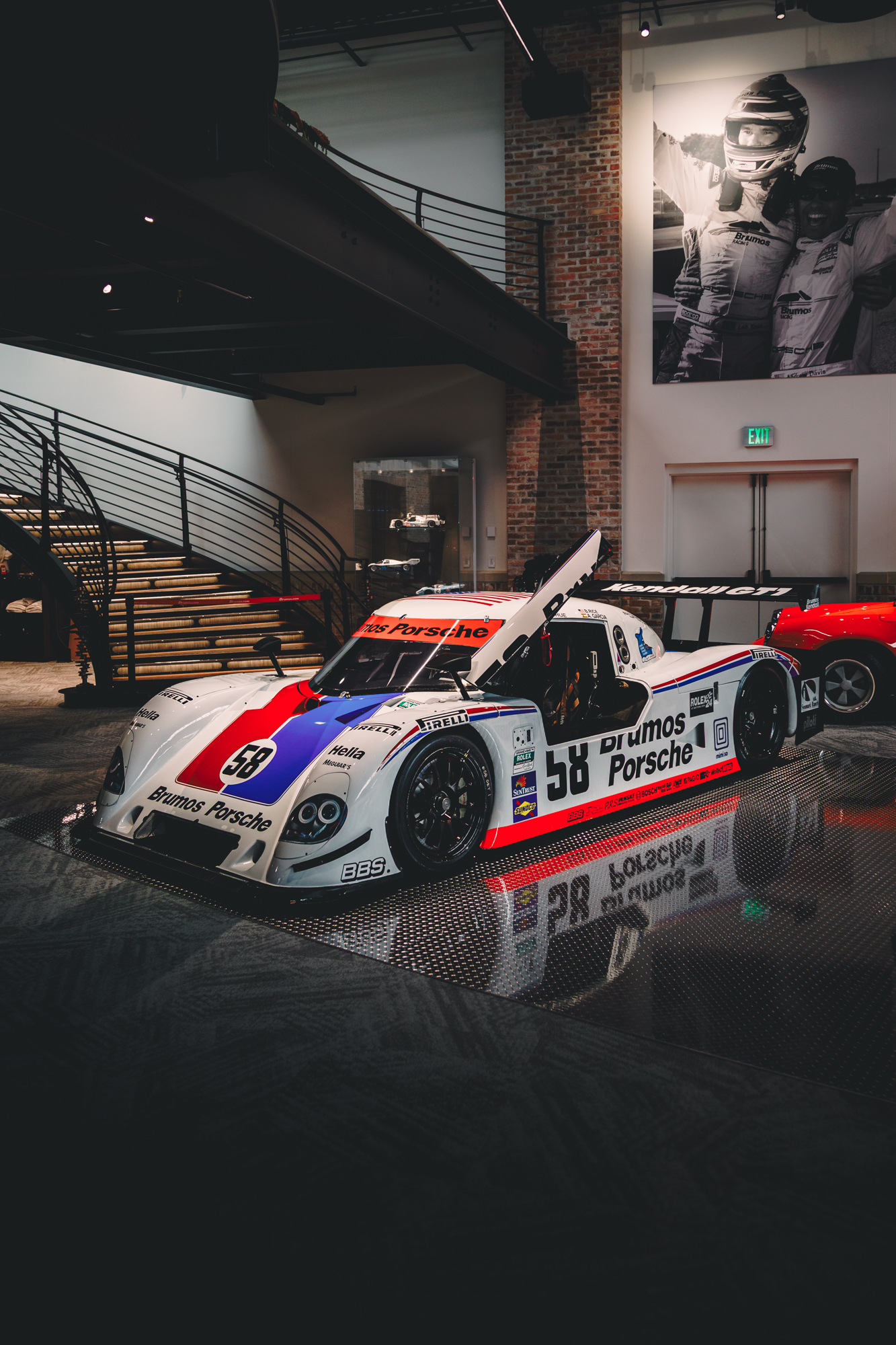

Beyond the headline cars, the Brumos Collection extends into defining moments of American sports car racing. On April 18, 1971, IMSA held its first sports car race at Virginia International Raceway. That event pitted a Porsche 914/6 GT driven by Haywood and Gregg against a 427-cubic-inch V8 Corvette driven by Dave Heinz. Haywood and Gregg’s victory secured their place in history as winners of the first IMSA Grand Touring race.

What ultimately sets the Brumos Collection apart is not just the depth of its cars, but how they are treated. This is not a museum of static relics. Every vehicle is maintained in running and driving condition. The collection contains more cars than can be displayed at once, with additional vehicles stored off-site. Displays are continuously rotated, ensuring that no two visits are ever quite the same.

Spanning three centuries of automotive history, the Brumos Collection delivers something rare: a living, breathing archive of motorsport culture. It is a place where design, engineering, and competition are inseparable—and where racing history is not only preserved, but actively respected.